SYSTEMS Rubik Cube solutions

Modern hockey systems are more than starting positions; they’re programmable operating models that shape ball circulation, pressing height, transition speed, and fatigue distribution. Choosing and adjusting a system requires aligning opponent structure, player profiles, and physiological readiness, then layering context‑specific build‑up and pressing behaviours on top (Elferink‑Gemser, Visscher, Lemmink, & Mulder, 2004; McGuinness & Sampaio, 2021).

It is a veritable Rubik’s cube for coaches and players alike and yet is routinely oversimplified or ignored by undertrained coaches. Multiple systems knowledge and application needs to be instilled in players from early teens.

The Most Common Systems

Obviously, there are many variations of these but that is what the game’s governing bodies in each geography are meant to provide as part of their coach development programs.

Let’s share the more widely understood and accepted strengths, vulnerabilities, and match‑ups typical of these systems.

4‑3‑3: The Positional Press

Shape: 4 defenders, 3 midfielders, 3 forwards

Strengths:

Creates midfield triangles for superior passing lanes and press resistance (Elferink‑Gemser et al., 2004)

Natural width stretches defensive blocks

Supports high‑intensity pressing when aerobic fitness is strong (Gabbett, 2010)

Risks:

Wide midfield spaces can be exposed if fullbacks overcommit

Outnumbered centrally vs. five‑man midfields; (e.g., 3‑5‑2)

Best vs.: 4‑4‑2 (central superiority), 3‑4‑3 (forcing wingbacks deep,isolate forwards)

Avoid vs.: 3‑5‑2 (central overload risk and and exposed counter‑lanes)

3‑5‑2: The Central Controller

Shape: 3 defenders, 5 midfielders, 2 forwards

Strengths:

Central dominance for tempo control

Wingbacks maintain width without losing central density

Flexible shifts between low block and mid‑press (Kempton, Sullivan, & Bilsborough, 2015)

Risks:

Wingback fatigue destabilises the system

Can be stretched by wide switches

Best vs.: 4‑3‑3 (midfield overload), 4‑4‑2 (breaking static lines)

Avoid vs.: 3‑4‑3 (wingback duels disadvantage)

4‑4‑2: The Compact Counter

Shape: 4 defenders, 4 midfielders, 2 forwards

Strengths:

Simple roles, with compact block means low cognitive load — useful for mixed‑experience squads (McGuinness & Sampaio, 2021)

Narrow defensive block reduces central penetration

Effective for direct play and counterstrikes; counter‑attacks are simplified and streamlined through twin strikers; with posting up ability crucial for these 2 roles.

Vulnerabilities:

Sustained possession and central rotation are limited; vulnerable to fast switches into wide overloads.

Risks:

Struggles in sustained possession

Vulnerable to switches of play into wide overloads

Best vs.:

3‑4‑3 (attack space behind wingbacks; force turnovers).

3‑5‑2 (pin the back three; disrupt the first phase).

Use with caution against:

4‑3‑3 (midfield outnumbering, width stress).

3‑4‑3 (wide aggressors)

3‑4‑3: The Wide Aggressor

Shape: 3 defenders, 4 midfielders (wingbacks), 3 forwards

Strengths:

Aggressive width and high regains; wingbacks manufacture overloads.

Disrupts possession rhythm of compact blocks

Effective for regaining ball high if aerobic thresholds are elite (Gabbett, 2010)

Risks:

Wingbacks bear extreme aerobic and decision‑making load; central counters hurt if midfield loses shape (Gabbett, 2010).

Central channels vulnerable to counters

Best vs.: 4‑4‑2 (wide overloads), 3‑5‑2 (pin wingbacks,isolating central mids)

Avoid vs.: 4‑3‑3 (midfield triangle exposure)

Morphing

In‑phase structural shifts that break presses

Elite hockey frequently “morphs” shape during buildup to distort opposition pressing schemes. The seminal published work on this comes from (Cuckow, 2014):

2‑3‑2‑3 (GB archetype)

Splits the team into two fluid units of five (attack/defence), encouraging a natural high press while retaining defensive balance. Flexible lending between units supports either phase but demands precise marking assignments (Cuckow, 2014).1‑3‑3‑3 (Dutch standard)

Pressing weaknesses resemble 4‑4‑2 when static, but Dutch sides typically cycle multiple presses and rotations to neutralise those gaps (Cuckow, 2014).Morph to 3‑4‑3

Defensive midfielder drops between centre backs, fullbacks step into midfield as wide mids, and wingers tuck to form a front three. Alternatively, a ball‑carrying centre back steps into midfield and continues forward as an inside forward—both methods create an extra forward target and rotation‑phase space but increase turnover risk (Cuckow, 2014).

Morph to 5‑3‑2/5‑2‑3

DM drops deeper than in the 3‑4‑3 morph to lure and stretch a well‑organised press, then release high‑speed outlets up the flanks. Requires high ball speed and fast forwards (Cuckow, 2014).3‑3‑4 (chasing state)

Paired with a full‑court press to flood the front line and accelerate verticality; maximises regain threats but is highly exposed to loss (Cuckow, 2014).3‑2‑2‑3

Non‑flat box/diamond midfield that creates natural interior space; relies on ball‑playing centre backs and a rotating, mobile midfield (Cuckow, 2014).

Coaching cue

Pre‑plan two morphs (e.g., 4‑3‑3→3‑4‑3 and 3‑5‑2→5‑3‑2) and tie triggers to opposition press cues (e.g., full‑back jump, pivot screen) to control when and where the press breaks.

Pressing taxonomy

Press choice sets the metabolic tone of the match and take a good deal of scenario-based training ahead of time with different rotations on the turf. It is typical to prepare 3 core levels, plus a trap variant (Cuckow, 2014; McGuinness & Sampaio, 2021):

Full‑court press

Maximum pressure. The German variant reassigns the “free” defender to cover the marker’s player; the marker steps to the CM’s man; CM steps to the spare defender in a 4‑back build‑up (or spare mid in a 3‑back). Everyone else man‑marks. Simple, effective, but metabolically expensive (Cuckow, 2014).Three‑quarter press

Defence and midfield man‑mark; front three slide across to block lanes in front of the ball, then jump on lateral circulation cues. Can be advanced to full pressure by splitting centre backs and releasing the opposite forward to attack the ball (Cuckow, 2014).Half‑court press

Used extensively ( albeit in an ad hoc half prepared way in most instances) Mark only in your half; the front three screen forward lanes. Lowest risk/energy, but invites opposition possession—best used to stabilise or to bait traps (Cuckow, 2014).Running press (trap from half‑court)

Lure defenders into poor structure, isolate the carrier, force a bad pass, and counter. Demands sharp timing and clear trap locations (Cuckow, 2014).

Programming note

Align press level with energy‑system targets and available rotation depth; reserve full‑court waves for momentum windows and set‑piece‑adjacent regains (Gabbett, 2010; Kempton et al., 2015).

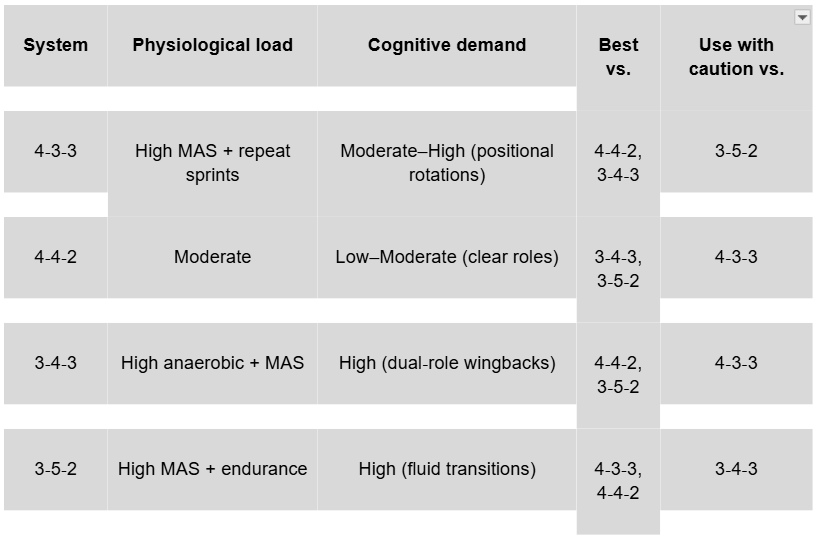

Playing Systems Summary Table

Note: Systems with wingbacks carry larger aerobic and decision‑making burdens; rotation depth and role clarity help prevent late‑game degradation (Gabbett, 2010; Kempton et al., 2015).

A Practical Deployment Guide

If opponent sits 4‑4‑2 low: Start 3‑4‑3 or morph 4‑3‑3→3‑4‑3 to create wide overloads; use three‑quarter press to keep counters in front (McGuinness & Sampaio, 2021; Cuckow, 2014).

If the opponent controls centre (3‑5‑2): Start 4‑3‑3 only if your pivot can break pressure; otherwise match with 3‑5‑2 and target diagonal switches to stress wingbacks (Kempton et al., 2015).

If chasing the game: Shift to 3‑3‑4 plus full‑court press in scripted 4–6 minute waves; accept turnover risk and prioritise regain‑to‑finish speed (Cuckow, 2014).

If opponent’s press is well‑drilled: Use draw‑the‑press morphs (e.g., 3‑5‑2/5‑3‑2) and pre‑planned exit lanes; rehearse the drop‑to‑DM timing and third‑man runs (Cuckow, 2014).

Bibliography

Cuckow, B. (2014, June 29). A guide to modern field hockey tactics. bcuckowanalysisandcoaching. https://bcuckowanalysisandcoaching.wordpress.com/2014/06/29/a-guide-to-modern-field-hockey-tactics/

Elferink‑Gemser, M. T., Visscher, C., Lemmink, K. A. P. M., & Mulder, T. W. (2004). Relation between multidimensional performance characteristics and level of performance in talented youth field hockey players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(11–12), 1053–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410400021575

Gabbett, T. J. (2010). The development and application of an injury prediction model for noncontact, soft‑tissue injuries in elite collision sport athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2593–2603. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f11f4d

Kempton, T., Sullivan, C., & Bilsborough, J. C. (2015). Match‑related fatigue reduces physical and technical performance in elite youth soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(14), 1406–1414. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.990486

McGuinness, A., & Sampaio, J. (2021). Tactical periodization in team sports: Theoretical foundations and practical applications. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 16(2), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954120970304