START it UP - CNS

Hockey is regularly lumped in with other “field invasion sports,” as if it shares the exact same neural demands as football or rugby. It doesn’t. It’s a sport where a hard projectile can travel faster than most athletes can process, manipulated via a one‑metre lever in a compressed space with 360° threats. That combination makes hockey one of the most Central Nervous System (CNS) ‑ hostile sports currently played. It is simply not football, and constantly copying and pasting sports science memes across to hockey is a seriously flawed practice.

Football clubs like Arsenal now use CNS‑priming warm‑ups that blend low‑load explosive work, scanning, and partner‑coordination drills to “switch on” the system without fatigue. That’s a great baseline. But for hockey, it’s not enough. This article builds the case—neuroscientifically and practically—for full‑range CNS activation in hockey as an integral part of training and pre-match priming of integrated body systems.

Hockey is an intermittent, high‑intensity sport characterised by repeated accelerations, decelerations, and multidirectional changes of direction layered over complex stick–ball actions.

The typical match exposes players to:

High frequencies of accelerate–brake–reorient sequences

Continuous tactical reshaping of space

Rapid transitions between low crouched and upright postures

Repeated fine‑motor stick manipulations at high speed

Additionally, the cognitive load of a competitive match is substantial. Malcolm et al. (2022) have shown that a single competitive field hockey match measurably altered players’ cognitive performance. Specifically, that a single competitive field hockey match impaired several aspects of cognitive performance immediately after play, including slower reaction times and reduced executive function.

Without sounding like Captain Obvious,player’s slower response times late in the game are down to acute CNS fatigue and reduced processing speed. Executive function tasks — which involve inhibition, switching, and working memory — showed:

reduced accuracy

slower performance

greater variability

These are classic signs of central fatigue and reduced cognitive control.

For the dedicated hive of sports sci undergrads that read this content, you will be pleased to know the authors also measured blood biomarkers before and after the match:

Adrenaline ↑

Noradrenaline ↑

Cortisol ↑

BDNF (brain‑derived neurotrophic factor) ↑

Cathepsin B ↑

These indicate:

high sympathetic activation

metabolic stress

acute neural plasticity signals

CNS load

eam‑sport matches impose high cognitive and physiological load repeated exposure could lead to cumulative cognitive fatigue

This underscores how demanding the sport is on the faculties of attention, working memory, and executive control.

It is not unreasonable or contrary to first hand experiences to realise hockey matches impose high cognitive and physiological load and that repeated exposure could lead to cumulative cognitive fatigue. Tournament play is the classic CNS exhaustion cauldron.

Decision density and neuromechanical chaos

Field hockey is an intermittent, high‑intensity sport with repeated accelerations, decelerations, and multidirectional changes of direction layered over complex stick–ball actions; (Agility 2021).

The typical match exposes players to:

High frequencies of accelerate–brake–reorient sequences

Continuous tactical reshaping of space

Rapid transitions between low crouched and upright postures

Repeated fine‑motor stick manipulations at high speed

Additionally, the cognitive load during competitive matches is substantial. Malcolm et al. (2022) showed that a single competitive field hockey match measurably altered players’ cognitive performance, underscoring how demanding the sport is for attention, working memory, and executive control.

Perceptual–cognitive work in youth and international hockey confirms the obvious lived reality: physical and technical qualities are necessary but not sufficient; decision‑making and perceptual–cognitive skills discriminate more clearly between higher and lower performers in fast‑paced contexts, Timmerman,Farrow,& Savelsbergh (2017); Drake & Breslin (2018).

Stick sports and extended interaction space

Unlike football, where the foot directly contacts the ball, a hockey player operates via a 1 m+ stick. This turns every action into a chained control problem: hand → wrist → forearm → shoulder → trunk → stick → ball → opponent → space. The neuromechanical literature on hockey stick speed and ball control shows that even “simple” drills entail high‑frequency, high‑speed stick–ball events that differentiate novices from state‑level players; Thiel, Tremayne & James. (2012).

From a CNS point of view, this means every decision is implemented through a distal tool, not a proximal limb. That matters for how the brain represents the body and space and how skills are acquired and executed.

The neuroscience of CNS priming and why it belongs in hockey

2.1 Cognitive priming during warm‑up

A recent open‑access study on cognitive priming during warm‑ups demonstrated that integrating cognitive tasks (e.g., reaction, decision, working memory) into physical warm‑ups can enhance sport and exercise performance via a “Goldilocks effect”—too little cognitive demand adds nothing; too much becomes detrimental, Díaz-García et al, (2025).

When cognitive load is tuned correctly, warmup becomes a neural preparation block rather than just a form of tissue temperature work or slowly boiling frog copy and paste coach syndrome.

Media summaries from the University of Birmingham and others have highlighted that this effect persists even under sleep restriction, meaning that well‑designed cognitive–physical warm‑ups can partially offset mental fatigue and sharpen readiness. This is crucial to bear in mind when planning a tournament campaign away from home. For a CNS‑dense sport like hockey, this is not a curiosity—it is a direct invitation to engineer warm‑ups that deliberately load perception, attention, and anticipation under controlled conditions.

Processing speed, reaction time, and decision time

Decision making in hockey is rarely limited by maximal strength or VO₂; it is limited by processing speed under spatiotemporal pressure. Cano et al. (2024) used decision‑time analysis to show that athletes’ processing speed during motor reaction tasks can be cleanly quantified and varies meaningfully across individuals.

Meta‑analytic work shows that anticipation is one of the strongest differentiators between elite and sub‑elite performers across sports (Song et al., 2025; Harris et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2024).

Decision‑making reviews in sport emphasize the roles of attention, prioritisation, and memory in high‑speed, dynamic environments—exactly the cognitive ecosystem of hockey circle defence or midfield interception.

Taken together:

CNS priming can acutely enhance performance when tuned correctly.

Processing speed and reaction time are trainable.

Decision‑making quality depends on how attention and memory are configured in the moment

Warm‑up, then, is an opportunity to shape the state of the body’s total systems, not just heat tissues and oxygenate or give the Assistant Coach something to do.

Perceptual–cognitive training improves anticipation and decisions

A systematic review and meta‑analysis of perceptual–cognitive training in team sports concluded that such training can meaningfully improve anticipation and decision‑making skills, Zhu et al, (2024). These interventions include video‑based occlusion tasks, small‑sided games, and various decision‑training paradigms that specifically load perception–action coupling and prediction.

In hockey, perceptual–cognitive load is not an abstract, academics-only construct. Field‑based work on perceptual–cognitive skills shows that elite players must rapidly filter relevant from irrelevant cues, interpret patterns of player and ball movement, and select actions within extremely compressed time windows. Complementary research on developmental histories in international hockey suggests that high‑performing players accumulate larger volumes of representative, decision‑rich activities during their development to enable faster and more effective discernment amidst the congested information intake.

Anticipation as perception–action coupling

Contemporary anticipation research has moved from static “reading” of cues to a more dynamic, perception–action coupling view. Huesmann and Loffing (2024) argue that anticipation is best understood as a tightly coupled perceptual–motor process that reduces motor costs under spatiotemporal pressure. This ability to anticipate movement patterns and their shifts in-game to respond optimally is a reflection of deeply ingrained probabilistic cues. The greater the volume, fidelity and relevance of preparatory problem solving patterns and effective outcome practice individuals are exposed to the richer the internal library of cognitive cues to draw upon for effective motor skill execution. In plain English, the more realistic the problem solving scenarios included in training and the better related these are to game time challenges, the greater the probability of the player acting optimally.

Overviews of anticipation under sport psychology emphasise that skilled athletes exploit early kinematic and contextual cues, gaining precious milliseconds to execute effective responses.In sport and exercise psychology, anticipation usually refers to the ability to quickly and accurately predict the outcome of an opponent’s action before that action is completed. Skilled athletes can use bodily cues to anticipate outcomes at earlier moments in an action sequence than can unskilled athletes, allowing them more time to perform an appropriate response in time-stressed tasks, Anticipation in Sport (2025). Anticipation is most commonly tested by occluding vision at a critical point in an action sequence, after which the observer must predict the action outcome. For instance, a tennis player may observe an opposing player performing a serve, but at the moment of racquet to ball contact, vision is occluded, and the receiver must predict the direction of the serve. Skilled players anticipate action outcomes based on events presented earlier in a movement pattern, providing an advantage for hockey skills execution that must be performed under severe time constraints. The selective occlusion of different body segments (e.g., the arms or legs) in video displays has shown that experts—when compared with novices—rely on the movement of body segments that are more remote from the end effector. For example, novice badminton players typically anticipate based on the movement of the opponent’s racquet, whereas skilled players use the movement of the opponent’s racquet and arm.

For hockey, this means:

The CNS warm‑up should load anticipation, not just reaction.

Drills that require real‑time scanning, direction changes, partner re‑synchronisation, and contextual decision‑making tend to more directly rehearse the anticipatory brain circuits that will be used in a game.

Sticks as tools

The neuroscience investigating tool‑use shows that when humans repeatedly use tools, the brain adapts its representation of the body and near space. Bruno et al. (2019) demonstrated that motor training with tools alters body metric representation, effectively reshaping how the system encodes reach and segment length. After enough repetitions with a stick:

the brain treats the stick as an extension of the arm,

the tip of the stick becomes part of the athlete’s peripersonal space,

and the nervous system encodes reach, angle, and segment length as if the stick were a biological limb.

The player can:

intercept balls earlier

deflect more accurately

trap cleanly without visual confirmation

Because the brain has extended its “reach map” to the stick head.When the stick is part of the body schema, the player can:

predict bounce angles

adjust grip micro‑timing

prepare the wrist/forearm for impact

This is why elite players look effortless in the chaos of a game.A player with a well‑adapted body schema can:

learn 3D skills faster

execute reverse‑stick skills earlier

manipulate the ball with finer control

Because the nervous system is no longer treating the stick as “external hardware.”

Conceptual and empirical work on peripersonal space—the region of space near the body in which interactions and threats are represented—shows that it is plastic, pragmatic, and extended by tools

Peripersonal space is the zone of space immediately around your body where your brain tracks:

opportunities (things you can reach, control, intercept)

threats (balls, sticks, bodies entering your space)

actions you can take right now

It is like a player’s action bubble. Our brain constantly reshapes the size and shape of your action bubble based on the context it finds itself in.

For a hockey player, this means:

When you crouch low, your bubble shifts downward.

When you accelerate, it stretches forward.

When you defend, it widens laterally.

When you’re tired, it shrinks.

Your nervous system is always redrawing the map. Your brain expands or contracts your action bubble depending on the task.

Examples in hockey:

When you’re pressing, your bubble expands forward to anticipate a tackle.

When you’re receiving, it narrows to focus on the ball line.

When you’re in the circle defending, it expands in all directions because threats come from 360°.

When you hold a hockey stick, your brain extends your peripersonal space along the stick.

In practical terms:

The tip of your stick becomes part of your “body map.”

Your action bubble now includes the full length of the stick.

You can sense and predict events at the stick head without looking.

You judge distances and angles as if the stick were a limb.

This is why elite players can:

poke‑tackle without looking

deflect balls with millimetre precision

trap balls arriving at awkward angles

intercept passes they “shouldn’t” reach

For the dedicated hockey player and coach, this literature is not abstract philosophy. It implies:

The stick becomes part of the functional body schema with sufficient practice.

The near space that must be monitored as “peripersonal” is extended out along the stick.

High‑speed decisions involve continuous estimation of stick angle, tip location, and contact probability, as well as threat mapping (e.g., lifted balls).

In practice, this means that CNS priming in hockey must integrate the stick as an embodied tool, not treat it as an add‑on after a generic physical warmup.

Representative hockey drills that combine scanning, stick‑contact constraints, partner interaction, and visual occlusion are exactly the sort of tasks that would be expected—on current body schema and peripersonal space models—to sharpen extended‑body representations before competition.

Candidate Routines

Non-Hockey Equipment Starters

Hand-Eye Wake Up

resources restricted to 2 x tennis balls per pair

Bosu Spike Ball

Resources = 1 Bosu ball per 4 users plus 1 -2 x tennis balls

Hockey Segue

Along with sharing these CNS activation routines I will see to it that I will kill the joy in your hearts by drilling down into the underpinning neuroscience and biomechanics; you know, the actual scientific rationale for optimising CNS for hockey.

The Back 9

Bag of white golf balls

Simple pass and receive evolved as follows:

3m, 5m,10, 20m apart simple forehand and backhand flat receives

Move to the Ball

Receive between flat markers ( 3m apart ) L→ R drag , R → L drag then concatenate these

Forehand and backhand aerial passes with receives on the full and bounced

The Sports Science Rationale

Increased Sensory Demand → Faster CNS Recruitment

A golf ball is:

smaller

harder

Lighter &

less predictable off the stick and turf.

This instantly increases the sensory resolution required from:

mechanoreceptors in the hands

proprioceptors in the wrist, forearm, and shoulder

visual acuity and tracking systems

dorsal stream processing (“where/how” pathway)

The CNS must up‑shift to handle the increased precision. This routine affords your players classic afferent priming which is best represented as

More sensory input → more neural drive → faster motor output.

Because the margin for error is tiny, the brain recruits:

higher‑threshold motor units

faster rate coding

tighter intermuscular coordination

This is the same principle we apply when using:

small‑ball tennis drills

juggling before sprinting

fine‑motor tasks before power tasks

The CNS becomes more excitable, meaning it fires faster and more synchronously.

This stands to potentially improve:

first touch

stick control

passing crispness

reaction speed

when you switch back to a normal hockey ball.

Enhanced Dorsal Stream Activation (Visual–Motor Pathway)

The dorsal stream handles:

motion tracking

spatial awareness

timing

interception

hand–eye coordination

A golf ball forces:

faster tracking

smaller visual angles

tighter peripheral monitoring

quicker predictive modelling

This is visual‑motor priming — the brain becomes more efficient at linking what the eyes see to what the hands do. When you return to a hockey ball, everything feels LARGER, slower and easier.

Increased Proprioceptive Load → Better Stick–Ball Control

Because the golf ball is harder and lighter, the stick receives:

sharper vibrations

faster feedback

more precise tactile information

This activates:

muscle spindles (detect stretch)

Golgi tendon organs (detect tension)

cutaneous receptors in the fingers and palm

This is proprioceptive up‑regulation.

The CNS becomes more sensitive to micro‑changes in stick angle, grip pressure, and ball movement.

Error Amplification → Faster Neural Adaptation

A golf ball punishes sloppy mechanics:

poor stick angle

late contact

heavy hands

slow reactions

This creates high‑value errors — mistakes that produce strong neural signals.

The CNS adapts rapidly because:

errors are clearer

corrections are immediate

feedback is sharper

This accelerates motor learning and primes the system for clean execution with a normal hockey ball.

Increased Cognitive Load → Faster Decision‑Making

A golf ball forces the brain to:

anticipate movement

adjust grip pressure

refine timing

maintain scanning while controlling a smaller object

This increases cognitive‑motor coupling, which is essential for:

receiving under pressure

passing in tight spaces

deception

quick release skills

Warm‑ups that increase cognitive load improve match‑speed decision‑making (Díaz‑García et al., 2025).

Switching Back to a Hockey Ball → Immediate Performance Boost

This is where your players will experience the “contrast effect.”

After handling a golf ball, a hockey ball feels:

slower

larger

easier to control

more stable

This creates:

smoother first touch

cleaner receptions

faster passing

better deception

The CNS stays in its high‑resolution mode, but the task becomes lower‑resolution — so performance jumps.

Using a golf ball in warm‑ups acts as a CNS primer because it:

increases sensory input

accelerates motor unit recruitment

activates the dorsal visual stream

heightens proprioceptive feedback

amplifies errors for faster learning

increases cognitive‑motor load

creates a contrast effect when switching back to a hockey ball

The result is a faster, sharper, more excitable nervous system — exactly what you want before high‑speed passing, receiving, and directional‑change work.

Thread Ball CNS Activation

Again a simple pass drill with obstacles and reauiring fundamental decisoin making competency that wil help fire up CNS.

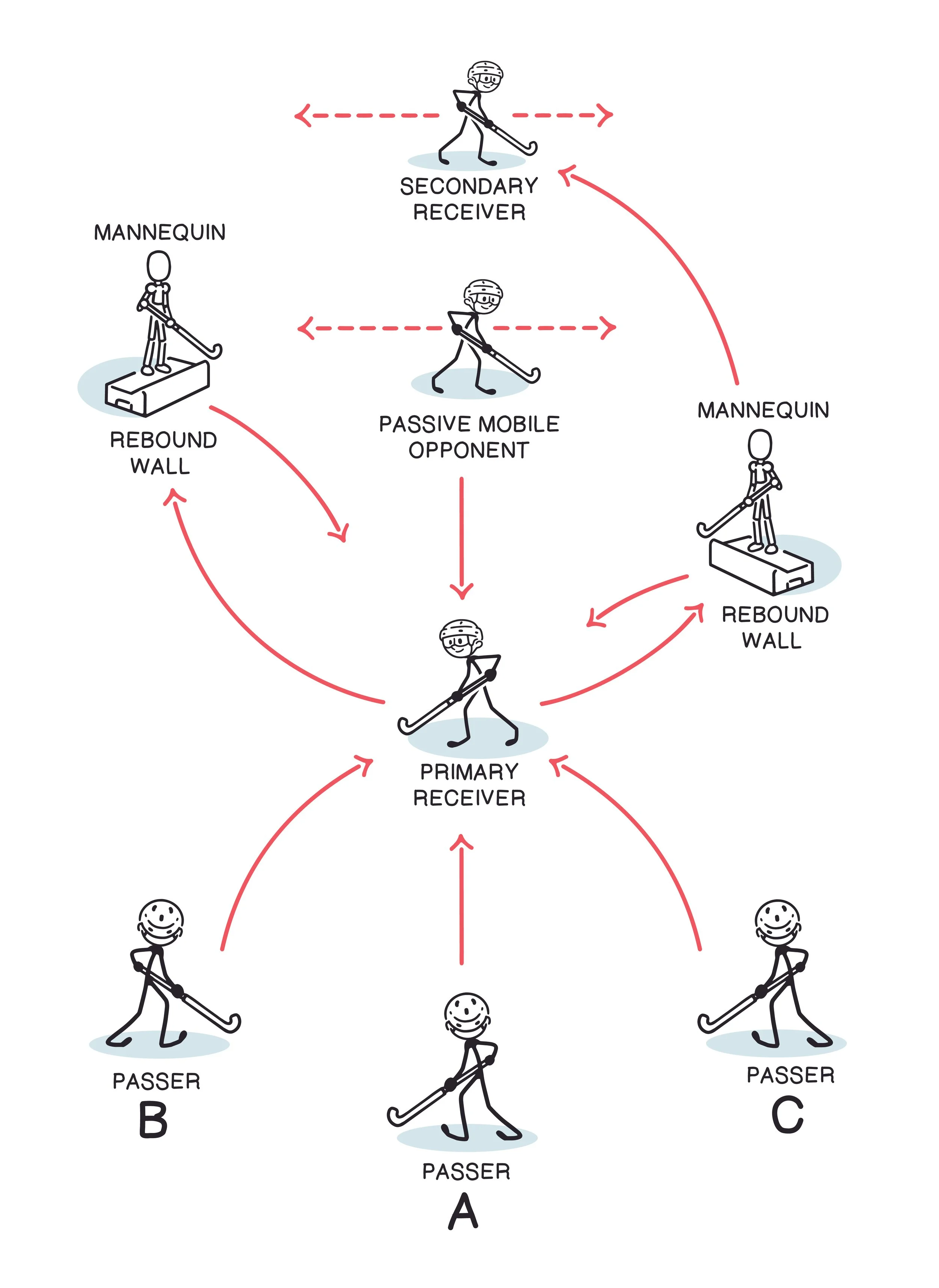

6 players per group

2 rebound walls-tyres with mannequins (optional mannequin)

Process

Prime Receiver (PR)

Receives a pass from Passer A,B or C moving to the ball to receive it rather than being stationary.

Upon receiving the ball they push a hard pass against the rebound wall-tyre with a mannequin and receive the rebounded return ball.

Upon receiving the rebounded ball you must thread a pass that misses the opponent in a colored bib who will jog across the passing lane between the first and a second rebound wall-tyre with a mannequin to a leading team mate who will move laterally across the space behind the second rebound wall-tyre.

Rotate roles after the PR has completed receiving at least 1 pass each from Passers A,B and C

The Science ( this may hurt the less technical )

This drill is far more than a passing pattern, it acts as a full‑stack neuromechanical activation task that loads:

visual perception

decision‑making

proprioception

CoM control

passing accuracy

timing

deception

movement preparation

reactive inhibition

and anticipatory control

…all inside a single, tightly‑designed sequence.

The First Receive

The ball can arrive from:

directly behind

left

right

This forces the receiving player to:

constantly scan

update spatial maps

adjust body orientation

prepare different receiving angles

move to the ball (not wait for it)

This activates the Dorsal Stream , sometimes referred to as the Where-How pathway. It handles motion tracking, spatial awareness, and movement guidance; comprising:

Superior Colliculus

Coordinates eye–head–body orientation toward the incoming ball.

Premotor Cortex

Prepares the receiving action based on the ball’s trajectory.

CNS Benefit

The brain must switch between three different receiving patterns. Switching = CNS priming. It increases neural excitability and readiness for match‑speed unpredictability.

Moving to the Ball to Receive

Tactically, this is to squeeze extra time and space for the receiver and possibly eliminate a marker. This enables

• CoM lowering

• foot placement

• deceleration control

• trunk alignment

• stick–ball–body integration

Biomechanically, this activates eccentric braking so the individual can slow and receive cleanly.

Hip–knee–ankle stiffness modulation is engaged to stabilise the body during the first touch.

Proprioceptive refinement is also tuned because the body must adjust to a moving ball, not a stationary one.

Rebound Pass to Tyre 1

This targets → Predictive Timing + Rate Coding

Passing into a tyre and receiving the rebound forces:

predictive modelling

timing

grip‑pressure modulation

micro‑adjustments in stick angle

rapid rate coding (fast motor unit firing)

The rebound is:

faster

less predictable

more angular

This increases:

Motor cortex activation

Because the player must prepare for a fast, hard return.

Cerebellar involvement

Fine‑tunes timing, error correction, and smoothness.

Proprioceptive load

Sharper vibrations through the stick → more sensory input → CNS up‑regulation.

Orange Bib Runner Crossing the Channel

This triggers → Reactive Inhibition + Decision‑Making

The orange bib player runs across the passing lane.

This forces the ball carrier to:

inhibit the instinct to pass early

delay action

adjust timing

maintain scanning

avoid tunnel vision

This loads:

Prefrontal Cortex

Decision‑making under time pressure.

Basal Ganglia

Reactive inhibition — stopping an action already prepared.

Dorsal Stream

Tracking moving obstacles.

This is a match‑realistic: defenders constantly cross passing lines.

Yellow Bib Receiver Appearing on Either Side

This encourages → Anticipation + Peripheral Vision

The yellow bib player appears:

left or right of the tyre

unpredictably

at variable timing

This forces the player to:

use peripheral vision

maintain head‑up posture

track two moving players

time the release

pass beyond the obstacle and the blocker

This loads:

Peripheral visual acuity

Critical for high‑speed passing.

Visuomotor integration

Linking what the eyes see to what the hands do.

Cognitive‑motor coupling

Processing movement while executing a technical skill.

Passing Beyond Tyre + Defender

This aims to elicit evolution of → Spatial Problem‑Solving + Kinetic Chain Organisation

The final pass requires:

angle selection

weight control

deception

stick‑face orientation

trunk rotation

kinetic chain sequencing

Biomechanically, this activates:

Pelvis–trunk counter‑rotation

To open the passing lane.

Ground reaction force redirection

To stabilise the body while passing around obstacles.

Fine‑motor control

To deliver a clean pass under cognitive load.

WHY THIS DRILL WORKS AS A CNS PRIMER

Because it loads:

perception (ball arrival from 3 angles)

movement (must move to receive)

timing (rebound unpredictability)

inhibition (orange bib crossing)

decision‑making (yellow bib location)

precision (final pass beyond obstacles)

anticipation (predicting movement patterns)

rate coding (fast stick control)

proprioception (stick vibrations + footwork)

This is a full‑stack neural activation drill.

It primes:

dorsal stream

cerebellum

premotor cortex

basal ganglia

motor cortex

proprioceptive pathways

The result is a player who is:

sharper

more aware

more stable

more reactive

more precise

more match‑ready

Hula Hoop CNS Activation

This is very, very simple and fun - enough to get things started pre-game or pre-session.

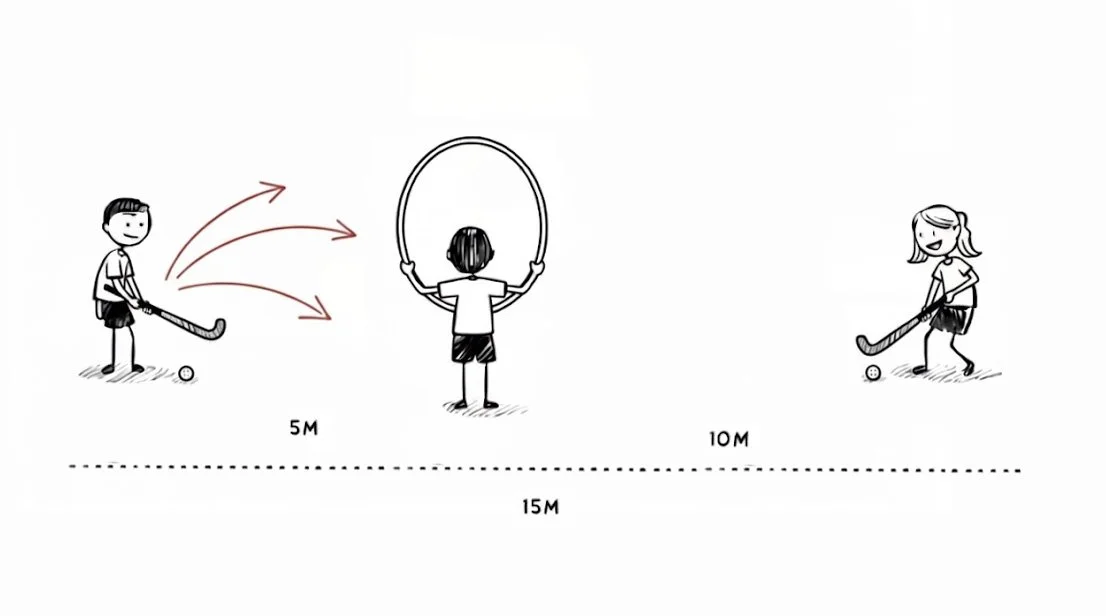

3 players per group

1 hula hoop

2 players stand 5m, 10m, 15m apart the 3rd player holds a hula hoop

The hoop holder dictates the pass type from:

1) over

2) through (ball must be passed at mid shin height )

3) under

keeping the hoop stationary for passes 1) and 2) and lowering the hoop to the point above the turf where a flat pass can pass easily under the hoop.

5 passes each from the 3 distances of 5n,10m and 15m before swapping roles

On the surface: a passing accuracy drill with a hula hoop. Under the hood we have a CNS activation task that forces:

• rapid perceptual categorisation (over / through / under)

• visuomotor mapping (different trajectories, same target)

• fine motor scaling (force, angle, stick path)

• distance‑dependent calibration (5, 10, 15 m)

It’s a solid example of low‑load, high‑neural‑density work.

Neuroscience perspective

Perceptual categorisation → faster decision channels

The hoop holder gives a variable-constraint:

Over → aerial / lifted trajectory

Through → flat, central channel to evade flat stick defensive posturing

Under → skimmed flat pass under a lowered hoop

Each cue forces the passer to:

rapidly classify the instruction

select a motor program

inhibit the others

That loads:

Prefrontal cortex: rule application (“over vs through vs under”)

Basal ganglia: action selection and inhibition

Premotor cortex: preparing the correct passing pattern

Over repeated reps, this drill sharpens stimulus → response mapping under simple but clear constraints.

Visuomotor integration → dorsal stream priming

The hoop becomes a visual gate.

The passer must:

judge hoop position in space

align stick path and ball trajectory

adjust for distance (5, 10, 15 m)

maintain accuracy while changing height and shape of the pass

That loads:

Dorsal visual stream (“where/how”) for spatial guidance

Cerebellum for timing and trajectory correction

Parietal cortex for integrating visual and proprioceptive input

You’re asking the CNS to run high‑resolution targeting at different distances and heights.

Error amplification → sharper neural adaptation

The hoop is unforgiving:

too low → hit the rim on “over”

too high / off‑line → miss “through”

too lifted → fail “under”

This creates clean, binary feedback:

success / fail

in / out

The CNS loves this—errors are obvious, corrections are immediate, learning is fast.

Biomechanical lens

Trajectory‑specific mechanics

Each pass type demands a different kinetic solution:

Over:

more wrist extension and forearm involvement

increased vertical force component

altered stick–ball contact point

Through:

pure linear drive

stable trunk

consistent follow‑through

Under:

low stick path

controlled, skimming contact

fine modulation of force to stay flat but fast

You’re training trajectory‑specific mechanics without over‑coaching them—constraints do the work.

Distance scaling → force and timing calibration

5 m vs 10 m vs 15 m:

same target

same hoop

different force, timing, and follow‑through

The passer must recalibrate:

force output (motor unit recruitment)

contact time on the ball

stick speed

release angle

This is graded motor control—a key feature of high‑level passing.

CNS activation value

Why this works beautifully as a CNS primer:

High neural load, low physical cost

Forces fast perception → decision → execution

Trains visuomotor precision at multiple distances

Uses simple constraints instead of heavy coaching

Builds passing adaptability (height, speed, angle)

You’re waking up:

dorsal stream

premotor and motor cortex

cerebellum

basal ganglia

proprioceptive pathways

Health DisclaimerThe information shared in this blog is for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult your primary healthcare provider before making any changes to your health, exercise, or nutrition routines — especially if you have existing medical conditions or concerns. We do not accept liability for decisions made based on this content. Your health journey is personal, and professional guidance is essential.