KNEE-jerk

Reaction time in hockey is a composite ability. It unifies sensory intake (seeing the ball early), perceptual discrimination, and neuromuscular execution under constrained time and space. We all know, it ain’t easy. Ageing reshapes these capacities, but targeted training can preserve performance. Evidence across sports vision, neuromuscular aging, and biomechanics reveals trainable levers at each link in the reaction chain: optical integrity, oculomotor control, perceptual-cognitive speed, neuromuscular transmission, and movement economy.

Physiological and Biomechanical Foundations

Sensory acquisition

Dynamic visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, peripheral awareness, depth perception, smooth pursuit, and saccades

These are rapid, jerky eye movements that shift your gaze from one point to another, allowing you to focus on a new object of interest. These movements are essential for visual exploration and bring the image of an object onto the fovea, the part of the retina with the highest visual acuity.

All act in concert to determine whether the ball is “seen early.” Aging reduces contrast sensitivity and increases visual processing latency (delay), but sports vision training can improve tracking and reaction time (Lochhead et al., 2024), even in masters players. It is one of the glaring omissions from masters training but no surprises there as a vast majority of individuals coaching masters players are well intentioned albeit untrained, ignorant muppets in all matters of sports science and psychology. Be rest assured, few, if any will read let alone comprehend and apply our content.

Perceptual-cognitive processing

Decision speed depends on selective attention and pattern recognition. Vision training and multi-object tracking accelerate cue detection and response selection (Poltavski & Biberdorf, 2014). Using golf balls for receiving, ensuring ball delivery is varied ( flat on turf, bouncing, various angles and trajectories) is a cheap, simple variation for imprinting game-like decision patterns that affect movement dictated by object tracking. It is bemusing to see warm ups for receives lacking in context let alone quality of pass. Throw different angles, flat, bounce, aerial receive on the move, under pressure and incorporate a simple receive elimination; rinse and repeat.

Neuromuscular transmission

Our speed lives in our wiring. As we age, signals from brain to muscle slow, blunting reaction and power. But targeted strength work, explosive drills, and recovery strategies can sharpen the transmission line. The nervous system remains trainable — and that’s where performance longevity lies.

Ageing influences motor unit recruitment, tendon stiffness, and rate of force development. These mechanisms slow initiation but are trainable via power-focused strength and plyometrics (Borzuola et al., 2020; Clark, 2023). Let’s dig down and illustrate what I mean here.

Ageing alters the neuromuscular system in several ways: motor unit remodeling reduces synchronous firing, tendon stiffness decreases elastic recoil, and rate of force development (RFD) slows (Borzuola et al., 2020; Clark, 2023).

In hockey, this shows as:

Delayed first step

When reacting to a sudden ball deflection, older players may hesitate or take longer to initiate the sprint. This may mean not getting into an optimal position to receive, resulting in missed passes or poor traps.

Slower stick repositioning

Neuromuscular latency reduces the speed of moving the stick from one intercept line-lane to another, especially under pressure. You can see where you need to be but your stick movement is delayed.

Reduced explosive push‑off

The jump or lunge to meet the ball is slower and less forceful. Part of the delayed first step reaction chain that deprecates so markedly when not trained.

Compromised recovery steps

After a receive, intercept, shot or tackle, the ability to quickly re‑center and get into the right position is diminished.

These delays are not inevitable nor as steep as they may see and feel; targeted strength and plyometric training can attenuate them.

Specific plyometric routines to restore RFD

Ageing influences motor unit recruitment, tendon stiffness, and rate of force development (RFD), which slows initiation in tasks such as the first step toward a deflected ball, rapid stick repositioning, or explosive aerial receptions. These mechanisms are trainable through targeted plyometrics (e.g., depth jumps, lateral bounds, reactive hurdle hops) and power‑focused strength routines (e.g., Olympic lift derivatives, trap bar jump squats, unilateral step‑ups), which restore tendon stiffness and rate of force development in ageing athletes (Borzuola et al., 2020; Clark, 2023).

Depth jumps

Step off a low box (20–30 cm), land, and immediately explode upward or laterally. This trains tendon stiffness and rapid stretch‑shortening cycle response.

Lateral bounds to stick reach

Jump explosively side‑to‑side, reaching with the stick to intercept a ball or cone. Add slow moving balls from variou angles, increase speed; vrowd he recieving space and progress each variable to ensure time and space are compressed. Mimics hockey’s lateral intercept demands.

Reactive hurdle hops

Small hurdles (20–40 cm) cleared in rapid succession, emphasizing minimal ground contact time. Improves neuromuscular reactivity.

Medicine ball slams with quick reset

Slam ball over head and or laterally, immediately recover stance and prepare for next slam. Trains explosive trunk power and rapid repositioning.

Strength routines to support neuromuscular speed

Olympic lift derivatives (hang power clean, high pull)

Moderate loads (30–60% 1RM) moved at maximal velocity. Builds explosive hip‑knee‑ankle extension.

Trap bar jump squat

Light loads (20–40% 1RM) with focus on bar speed. Enhances vertical RFD for aerial ball reception.

Split‑stance Romanian deadlifts with banded resistance

Improves tendon stiffness and unilateral stability, critical for quick directional changes.

Unilateral step‑ups with explosive drive

Weighted step‑ups emphasizing rapid concentric phase. Trains single‑leg push‑off for first‑step acceleration.

Integrated hockey‑specific drills

Ball‑drop sprint

Partner drops ball unpredictably; player reacts with immediate sprint. Trains visual cue recognition + explosive initiation. Distances need be no more than 3-5m; ensure thorough warm-up beforehand.

Reaction shuffle‑catch

Lateral shuffle with random direction call; player must reposition stick instantly. Combines neuromuscular speed with perceptual reaction.

Contrast sprints

Random start cues (light or sound) trigger short sprints. Reinforces stimulus‑response speed under fatigue.

Movement economy

Movement economy refers to the efficiency with which an athlete organizes footwork, posture, and stick pathing to minimize wasted motion and reduce intercept time. Efficient footwork and stick pathing shave precious milliseconds off intercepts. But ageing joints and reduced flexibility change the equation. The good news? Stance tweaks, mobility drills, and sequencing work can restore economy and keep you moving sharp…In hockey, this means fewer corrective steps, optimal stance width, and direct stick trajectories toward the ball.

Movement economy declines with age because of reduced flexibility, altered neuromuscular sequencing, and diminished proprioception increase the probability of wasted motion and latency in footwork and stick pathing. This slows intercept time in hockey, particularly when adopting low stances or repositioning rapidly. Targeted interventions—including mobility drills for hips and ankles, strength routines emphasizing joint sequencing, balance training, and stick pathing optimization—can attenuate these deficits and preserve efficient movement economy in aging athletes (Núñez-Lisboa et al., 2023).

How and Why Decline Occurs

Flexibility and joint stiffness

Ageing reduces elasticity in connective tissues and alters muscle-tendon compliance, limiting hip and ankle range of motion (Núñez-Lisboa et al., 2023). This restricts low stance adoption and quick directional shifts, forcing extra steps or slower repositioning.

Coordination and sequencing

Sub-optimal motor unit remodeling and slower neuromuscular firing disrupt the timing between hip, knee, and ankle extension. This results in inefficient sequencing during acceleration or lateral shuffles, increasing intercept time.

Postural control

Declines in proprioception and balance reduce stability in wide stances which hockey depends upon for optimal movement patterns. Older players tend to compensate with narrower bases, which lengthens time to intercept ground balls or aerial receptions. This also compromises directional change and with it, agility.

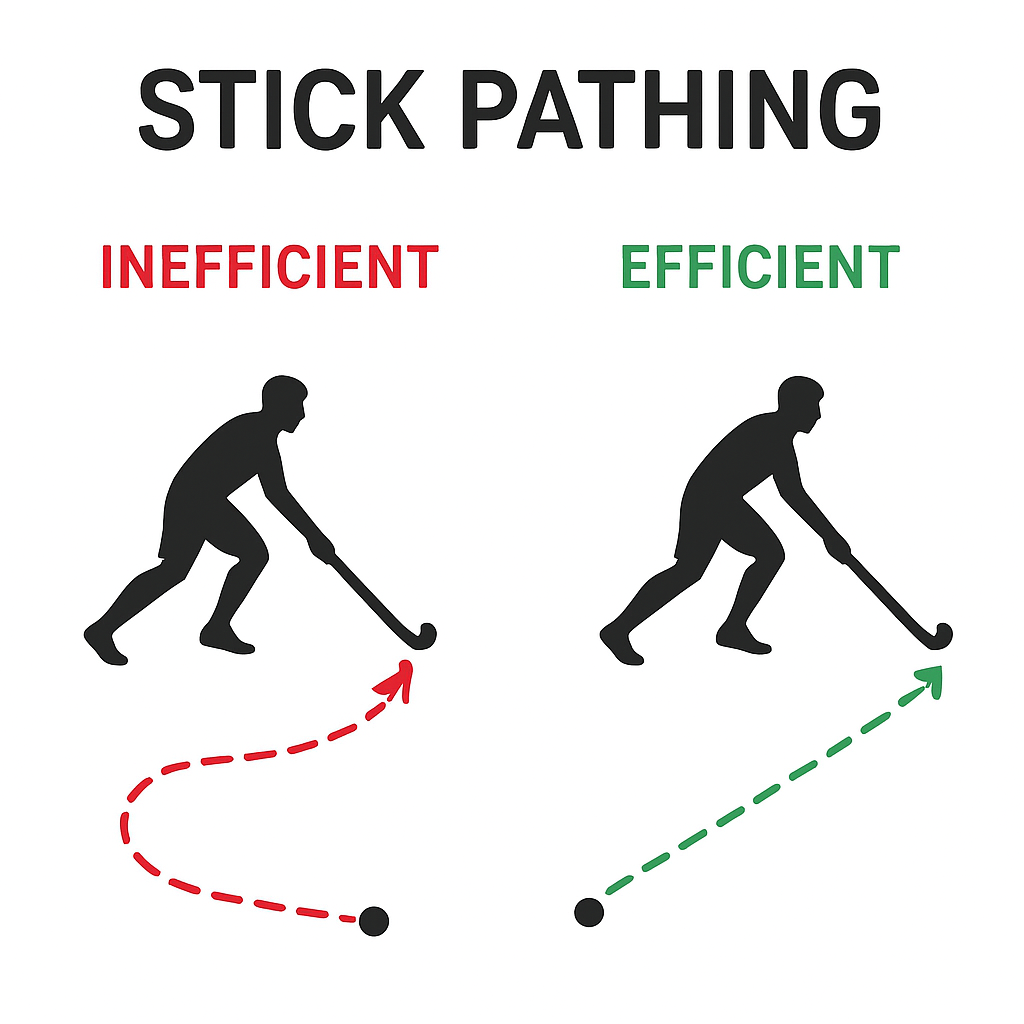

Stick pathing inefficiency

Stick pathing refers to the trajectory and efficiency of the stick’s movement when intercepting, receiving, or redirecting the ball. It’s essentially the “path” your stick head takes from its starting position to the point of contact with the ball.

Why It Matters

Time efficiency

A direct, economical stick path reduces milliseconds between visual cue recognition and ball contact.

Error reduction

Shorter, straighter paths minimize overshooting or looping, which can cause missed receptions.

Energy economy

Efficient pathing reduces unnecessary shoulder/trunk rotation, conserving energy over long matches.

Biomechanical synergy

Proper pathing aligns with hip/ankle sequencing, allowing smoother intercepts without destabilizing stance.

Age‑related Decline

Reduced shoulder mobility

Older players may compensate with wider arcs instead of direct stick paths.

Slower trunk rotation

Neuromuscular decline can cause looping movements rather than crisp, economical intercepts.

Proprioceptive lag

Less precise spatial awareness leads to “over‑correction” in stick movement.

Interventions to Improve Stick Pathing

Wall tap drills

Rapid stick taps against fixed wall targets at different heights and distances from your centred base included one handed reaches. This may assist train direct paths.

Cone intercepts

Place cones in staggered lanes; move stick directly between them without looping then repeat with the ball.

Partner feed drills

Partner rolls or flicks balls ( hockey, golf and tennis ) unpredictably; focus on shortest stick trajectory to intercept.

Mobility support

Shoulder dislocates with bands, thoracic rotations, and scapular control drills to restore range.

Video feedback: Record intercepts and analyze stick trajectory — aim for straight lines, minimal detours.

Suggested Attenuation via Intervention

Flexibility & Mobility Training

Dynamic hip openers

Walking lunges with rotation, hip circles, and deep squat holds.

Ankle dorsiflexion drills

Calf stretches against the wall, banded ankle mobilizations.

Thoracic mobility

Cat-cow, seated rotations, foam roller extensions.

Why: Tehse help restore range of motion, enabling wider stances and quicker directional changes.

Strength & Power Sequencing

Split squats with stick reach

Train hip-knee-ankle sequencing while mimicking intercept posture.

Lateral resisted shuffles

Bands around waist to overload footwork economy; vary footwork patterns so they mimick in game movements precisely.

Trap bar deadlift with fast concentric

Reinforces hip drive and sequencing efficiency.

Why: Builds coordinated power across joints, reducing wasted motion.

Balance & Proprioception

Single-leg stance with stick intercepts

Balance on one leg while reaching with a stick to catch rolling balls.

Reactive balance drills

Partner pushes or BlazePod cues while maintaining stance. Mind you procuring a BlazePod or similar is a club-association resourcing task. Still, its a valuable tech tool.

Why: Improves stability in wide stances, reducing corrective steps.

Mitigating Preconditions in Age-related Reaction Time Decline

Seeing the ball early is half the battle. Age can slow oculomotor control and visual discrimination, but targeted vision drills and sports‑specific cues keep your eyes ahead of the play. Trainable levers exist at every stage of the visual chain.

Optical

Uncorrected refractive error, reduced contrast sensitivity, and oculomotor inefficiencies increase “late seeing” by blurring ball edges, delaying detection against complex backgrounds, and slowing eye movements. These changes occur due to age‑related declines in accommodative capacity, retinal processing, and oculomotor coordination. Targeted interventions—including annual sports optometry screening, contrast sensitivity drills, and oculomotor training—can attenuate these deficits and preserve early ball detection in ageing hockey players (Rajeshkumar, 2023; Lochhead et al., 2024; Poltavski & Biberdorf, 2014; Polikanova et al., 2024).

Age‑related optical and oculomotor decline: Why “late seeing” occurs

Uncorrected refractive error

What it is

Subtle myopia, hyperopia, or astigmatism that is not corrected with lenses. Even small errors blur the ball’s edges, especially at speed or distance.

Why it occurs

Ageing eyes lose accommodative capacity (presbyopia), making near‑to‑far focus transitions slower and less precise (Lochhead et al., 2024).

Impact in hockey

A ground ball skimming across turf may appear blurred or delayed, reducing the time available for stick positioning.

Reduced contrast sensitivity

What it is

The ability to detect objects against backgrounds of similar luminance. Declines with age due to changes in retinal processing and lens transparency (Poltavski & Biberdorf, 2014).

Why it occurs

Age‑related yellowing of the lens and reduced retinal ganglion cell efficiency diminish contrast discrimination.

Impact in hockey

A white ball against bright turf or a lofted ball against a cloudy sky may be detected later, delaying reaction.It also renders older age group games played under lights more problematic than usual.

Oculomotor inefficiencies

What it is

Slower or less accurate saccades (rapid eye movements) and smooth pursuit (tracking).

Why it occurs

Ageing reduces neural conduction velocity and coordination of extraocular muscles (Polikanova et al., 2024).

Impact in hockey

Late saccades to a deflected ball or inaccurate pursuit of aerial passes increase “late seeing” and missed receptions.Not only dooes it uptock the number of errors but also putsolder players at greater risk of injury.

Targeted interventions to attenuate “late seeing”

Optical correction and screening

Annual sports optometry exams are useful to detect refractive errors and prescribe corrective lenses (Rajeshkumar, 2023).Consider tinted or contrast‑enhancing lenses for turf and sky conditions. Also investigate regular dynamic visual acuity testing to monitor decline.

Contrast sensitivity training

Variable ball drills

Use balls of different colors (white, orange, yellow) against varied turf backgrounds.

Contrast boards

Athletes identify letters/numbers of decreasing contrast under time pressure.

Lighting variation drills

Train under bright and dim conditions to harden contrast detection.

Oculomotor training

Saccade grids

Rapid eye movements between randomized letters/numbers on a wall chart.

Smooth pursuit arcs

Track a moving ball or laser pointer along semicircular paths. Join in with your cat and dog.

Peripheral cue drills

Respond to stimuli appearing at the edge of vision, forcing rapid saccade‑to‑pursuit transitions.

Integrated hockey drills

Ground ball anticipation

Coach feints before passing; athlete performs anticipatory saccade to entry lane.

Aerial arc prediction

Vary release points on turf ( circles, near corner flags etc ) angles and speeds; player tracks and intercepts.

Crowded lane occlusion

Train in traffic with partial visual obstruction to sharpen cue prioritization.

Ground vs Aerial Reception

Ground balls

Require anticipatory saccades, low stance, and stick pre-positioning. Opponent cues (stick angle, spin) inform early intercept (Polikanova et al., 2024).

Aerial balls

Demand depth perception and saccade-to-pursuit transitions. Midline stabilization and footwork triangles reduce parallax errors.

Evidence-Based Interventions

Sports vision training

This method enhances visual sensitivity by strengthening neural pathways for contrast detection, improves tracking by refining oculomotor control of saccades and smooth pursuit, and sharpens hand‑eye coordination by accelerating sensorimotor integration between visual cues and motor responses. These adaptations occur because repeated exposure to dynamic, unpredictable stimuli forces the visual and neuromuscular systems to reduce latency and improve precision under game‑like conditions (Lochhead et al., 2024; Polikanova et al., 2024; Poltavski & Biberdorf, 2014).

How and why sports vision training works

Visual sensitivity

• Mechanism

Sports vision drills expose the visual system to progressively faster and lower‑contrast stimuli, forcing the retina and visual cortex to process signals more efficiently.

• Why it works

Repeated exposure strengthens neural pathways for contrast detection and dynamic acuity, reducing latency in recognizing the ball against complex backgrounds (Lochhead et al., 2024).

• Practical example

Reading letters on a dynamic acuity chart while moving the head trains the eyes to maintain clarity during motion, directly improving ball recognition during fast play.

Tracking ability

Mechanism

Smooth pursuit and saccade drills train the oculomotor system to lock onto moving targets and shift gaze rapidly between cues.

Why it works

These exercises improve coordination between extraocular muscles and cortical control centers, reducing overshoot and lag in eye movements (Polikanova et al., 2024).

Practical example

Following a ball along unpredictable arcs or shifting gaze between random grid points mimics hockey’s demands of tracking deflections and aerial passes.

Hand‑eye coordination

Mechanism

Linking visual stimuli to immediate motor responses (catching, intercepting, reacting to lights) strengthens sensorimotor integration.

Why it works

The brain learns to shorten the time between visual cue recognition and neuromuscular execution, enhancing reaction speed (Poltavski & Biberdorf, 2014).

Practical example

BlazePod or light‑reaction drills where athletes must tap or intercept based on unpredictable visual cues replicate the split‑second decisions required in hockey.

Unified Training Reaction Speed and Acuity Program (12 Weeks)

Block 1 (Weeks 1–4): Foundations

Vision drills: dynamic acuity ladders, saccade grids.

Cognitive drills: multi-object tracking, reaction lights.

Neuromuscular: jump squats, lateral bounds.

Block 2 (Weeks 5–8): Integration

Ground-ball contrast drills, anticipatory saccades.

Aerial arc prediction, saccade-to-pursuit transitions.

Power: Olympic pulls, depth jumps.

Block 3 (Weeks 9–12): Chaos and Occlusion

Crowded lane passes, occlusion drills.

Mixed ground/air feeds under fatigue.

Reactive sprints and unilateral bounds.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Apex Hockey. (2024). Reaction time training for hockey: The OODA Loop.

Borzuola, R., Giombini, A., Torre, G., Campi, S., Albo, E., Bravi, M., Borrione, P., Fossati, C., & Macaluso, A. (2020). Central and peripheral neuromuscular adaptations to ageing. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(3), 741.

Clark, B. C. (2023). Neural mechanisms of age-related loss of muscle performance and physical function. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 78(Suppl 1), 8–13.

Impact Hockey. (2024). Improve scoring & game-time reaction skills: 3-tire read & react drill [Video]. YouTube.

Lochhead, L., Feng, J., Laby, D. M., & Appelbaum, L. G. (2024). Training vision in athletes to improve sports performance: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology.

Mendonça, G. V., Pezarat-Correia, P., Vaz, J. R., Silva, L., & Heffernan, K. S. (2017). Impact of aging on endurance and neuromuscular physical performance: The role of vascular senescence. Sports Medicine, 47, 583–598.

Núñez-Lisboa, M., Valero-Bretón, M., & Dewolf, A. H. (2023). Unraveling age-related impairment of the neuromuscular system: Biomechanical and neurophysiological perspectives. Frontiers in Physiology, 14, 1194889.

Polikanova, I. S., Sabaev, D. D., Bulaeva, N. I., Panfilova, E. A., & Leonov, S. V. (2024). Analysis of eye and head tracking movements during a puck-hitting task in ice hockey players. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 17(3). Poltavski, D., & Biberdorf, D. (2014). The role of visual perception measures used in sports vision programmes in predicting actual game performance in Division I collegiate hockey players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 32(17), 1680–1692.

Rajeshkumar, K. (2023). Investigation of the changes in reaction time due to the effect of sports vision training among hockey players. Indo American Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Review.

Hockey Training. (2019). Improve your hockey reaction time [Video]. YouTube.

BlazePod. (2025). Drills to improve reaction time in hockey with a partner [Video]