Think before Deciding

The role of the modern coach has expanded far beyond technical instruction. In contemporary hockey — and across comparable invasion sports such as football, rugby sevens, and lacrosse — coaching has become a form of systems architecture. Coaches must integrate biological readiness, tactical demands, psychological states, social dynamics, and long‑term development pathways into a coherent decision framework, often under time pressure and with incomplete information.

This shift reflects broader trends in high‑performance sport:

the explosion of athlete monitoring technologies

the rise of multi‑disciplinary support teams

the increased psychological and social complexity of modern athletes

the expectation of evidence‑based decision making

As Lyle (2002) notes, coaching is now a “complex decision‑making environment,” and cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988) helps explain why coaches often feel overwhelmed. The volume of information has increased, but human cognitive capacity has not.

To understand this landscape, we begin with a number of major decision streams that define modern coaching.

MAJOR DECISION STREAMS IN MODERN COACHING

Tactical & Strategic Decisions

Tactical decisions — pressing structures, outletting patterns, penalty corner units, in‑game adjustments — rely on prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampal networks responsible for planning, pattern recognition, and scenario simulation Kahneman, (2011); Klein, (1998).

Under high information load — multiple data streams, time pressure, emotional intensity — the prefrontal cortex (PFC) can struggle to simulate tactical futures.

This leads to:

conservative decisions (e.g., “just hold shape”)

heuristic shortcuts (e.g., “play safe”)

delayed reactions

missed opportunities

This is not a failure of coaching — it’s a bit of a neural bottleneck. The brain’s deliberate reasoning system (System 2) is slow, effortful, and easily disrupted under stress Kahneman, (2011).

Use Pre‑Defined Tactical Triggers

Pre‑defined tactical triggers are if–then decision rules that shift in‑game choices from slow simulation to fast recognition.

They work by front-loading the decision logic so that during the game, the coach or athlete can act based on pattern matching, not deliberation.

These triggers are pre-agreed, contextual, and limited in number (ideally 5–7 per game plan). They reduce cognitive load and increase tactical clarity.

Mitigation

Use pre‑defined tactical triggers to shift in‑game decision making from slow, effortful reasoning to fast, pattern‑based recognition Chase & Simon, (1973). This switch is enabled and supported by chunking and recognition-primed decision making Klein, (1998); Chase & Simon, (1973).

Here’s how it works:

Pre-game encoding

Coach and players rehearse specific tactical triggers.In-game cue detection

A known pattern emerges (e.g., opposition DM receives the ball unpressured).Pattern match

The brain retrieves the associated action without needing full simulation.Execution

The decision feels “intuitive” but is actually pre-loaded logic.

This is the same mechanism elite chess players use to recognize board states instantly; Chase & Simon, (1973) — and it’s trainable.

A dugout-accessible video library of searchable game scenarios is a powerful decision-support tool to assist in optimising tactical triggers.

Why it works

Reinforces pattern recognition

Builds shared mental models

Accelerates cue–response learning

Supports staff alignment under pressure

Design principles

Short clips (10–20 seconds)

Thematic tagging (e.g., “trap press trigger”, “fatigue sub cue”)

Outcome overlay (e.g., “successful”, “neutral”, “costly”)

Searchable by game phase, opponent, or trigger type

Physical Preparation & Load Management Decisions

Load management requires interpreting GPS metrics, HRV, sprint profiles, and recovery data. These decisions rely heavily on working memory, which is extremely limited Sweller, (1988).

Excessive metrics increase cognitive load and reduce decision accuracy.

Mitigation

Adopt a 3–5 metric rule, focusing only on indicators that directly influence decisions Impellizzeri et al., (2019). Use visual summaries (traffic lights, trend lines) to reduce cognitive burden.

Field hockey is a high‑intensity, repeat‑effort, multi‑directional, tactical‑fluid sport.AS a coach you need to juggle time efficiency, self energ and clarity as well as decision effiacy.

So any metrics that are agreed and defined must reflect:

readiness

fatigue

tactical capacity

injury risk

in‑game decision support

From the evidence base Impellizzeri et al., (2019); Gabbett, (2016) and real-world elite practice, the 3–5 metrics that actually influence decisions to a large extent in a game like hockey are:

High‑Speed Running (HSR) or High‑Intensity Distance (HID)

Why it matters

Strong predictor of fatigue and soft‑tissue injury risk

Directly tied to pressing, counter-pressing, and transition play

Midfielders and strikers rely heavily on this capacity

Decision influence

Sub rotations

Pressing strategy

Tactical simplification late in games

Accelerations & Decelerations (Acc/Dec Load)

Why it matters

Stronger predictor of neuromuscular fatigue than distance

Reflects defensive intensity, counter-pressing, and tight-space work

High deceleration load correlates with groin/hamstring risk

Decision influence

Adjusting defensive structures

Managing high-load defenders

Subbing fatigued midfielders before breakdowns occur

Heart Rate Recovery (HRR) or Heart Rate Exertion Index

Why it matters

Fast indicator of acute fatigue

Reflects readiness to repeat high-intensity efforts

More stable than HRV in tournament settings

Decision influence

Sub timing

Identifying players who cannot sustain tactical demands

Adjusting training intensity next day

Subjective RPE

Why it matters

Easily understood & tracked

Captures internal load that GPS cannot,

Reinforces trust and respect for athlete self-management

Strong predictor of overreaching

Helps detect “silent fatigue” (psychological + physiological)

Decision influence

Adjusting training load

Identifying players masking fatigue

Protecting key players in congested schedules

Acute Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR)

A simplified version is best.

Why it matters

Helps identify elevated injury risk windows

Useful for tournament play and return-to-play

Decision influence

Restricting minutes

Adjusting training intensity

Modifying tactical roles (e.g., less pressing)

We like to work with these factors as they

Directly influence decisions

Predict performance capacity

Predict probable injury risk.

They are stable and interpretable under pressure and can be acted on immediately. Everything else (heatmaps, total distance, HRV, wellness scores) is more about context than decision‑pathed.

Audible Alerts

You could consider audible alerts to be used when thresholds are hit, but only for first‑order metrics. These can be useful as under match pressure, coaches and analysts experience:

attentional narrowing

cognitive overload

reduced working memory

reduced ability to monitor dashboards

Audible alerts act as an external cognitive framework, allowing the coach to:

maintain tactical focus

avoid constant screen-checking

respond instantly to risk thresholds

make decisions based on pre‑defined logic

This aligns with human factors research in aviation and military decision systems.

Some first‑order, decision‑critical thresholds to consider:

HSR threshold exceeded

→ “Player X approaching fatigue risk zone.”

HRR failure after repeated efforts

→ “Player Z not recovering between efforts.”

RPE spike

→ “Player reports high internal load.”

ACWR red zone

→ “Player entering elevated injury risk window.”

These alerts should be:

rare (no more than 3–5 per match)

pre‑defined

actionable

linked to tactical or substitution decisions

What to consider as Trigger Alerts?

Total distance

Heatmaps

HRV

Wellness scores

Technical stats

“Interesting but not actionable” dat

A “3–5 + Alerts” Model

Here’s a starting point structure for coaching MIS :

Track 3–5 first‑order metrics

(HSR, Acc/Dec, HRR, RPE, ACWR)

Set pre‑defined thresholds

(based on position, player profile, injury history)

Use audible alerts only for threshold breaches

(no more than 3–5 per match)

Link alerts to tactical or substitution actions

(“If X → then Y” logic)

Psychological & Behavioural Decisions

Psychological readiness is one of the most misjudged components of athlete selection because it relies on a coach’s ability to accurately read confidence, motivation, stress, and emotional stability — all of which activate complex social‑cognition and affective‑processing networks in the brain. Research shows that when coaches evaluate athletes under pressure, they unconsciously draw on heuristics rather than objective cues, especially when cognitive load is high (Arnold & Fletcher, 2012). In these moments, subtle emotional signals — hesitation, frustration, quietness, over‑arousal — are easily misinterpreted.

A tired or stressed coach may read an athlete’s anxiety as lack of confidence, or interpret focused seriousness as disengagement. Under cognitive overload, the prefrontal cortex’s regulatory capacity drops, and coaches default to fast‑thinking, blunt communication, and simplified narratives about players (“she’s not ready,” “he’s inconsistent,” “she’s mentally fragile”).

These snap judgments are rarely malicious ( although they may be spoken aloud and seem a tad harsh ) — they’re neurological shortcuts — but they create fertile ground for confirmation bias, where early impressions harden into fixed beliefs. The result is a selection environment where psychological factors are assessed inconsistently, emotionally, and often inaccurately, despite being among the most influential determinants of performance under pressure.

Mitigation

Use brief, structured psychological check‑ins to externalise athlete state and reduce interpretive burden Reardon et al., (2019). These check‑ins only need 2–3 questions preferably with standardized and validated scales to identify red flags without overwhelming athletes or staff. Integrate findings into selection and communication plans.

We recommend the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire (APSQ‑10); Rice et al., (2020), that has been in use for some time and designed specifically for fast, routine screening.

Developed by Rice et al.

Validated in elite male and female athletes

Measures:

Self‑regulation

Performance concerns

External coping

Selection & Role Assignment Decisions

These decisions activate the brain’s core risk–reward circuitry, particularly the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex — regions responsible for evaluating uncertainty, predicting outcomes, and weighing potential gains against potential losses. Under ideal conditions, these systems integrate multiple streams of information: tactical fit, recent performance, psychological readiness, and long‑term development potential. But when coaches are fatigued, stressed, or cognitively overloaded, these neural systems shift into a risk‑averse, short‑term mode (Baumeister, 2013).

This lean toward safety leads coaches to favour familiar athletes, predictable behaviours, and low‑variance choices, even when those choices are not optimal for team performance or athlete development. In this state, the brain prioritises certainty over accuracy, defaulting to players who feel “safe” rather than those who may offer higher upside.

You only have to look at the repeat selections of incumbent coaches in international masters teams to see how prevalent and self-destructive this behaviour is. This is where selection bias becomes most potent: the coach’s internal stress state quietly narrows the decision frame, suppresses creativity, and reinforces existing hierarchies.

The result is a selection environment where long‑term potential is undervalued, experimentation is avoided, and role assignments become conservative rather than strategic.

Mitigation

More thoughtful selection of coaches including an insistence on a tertiary qualification in sports science or equivalent. But more detail on this justifiable rant.

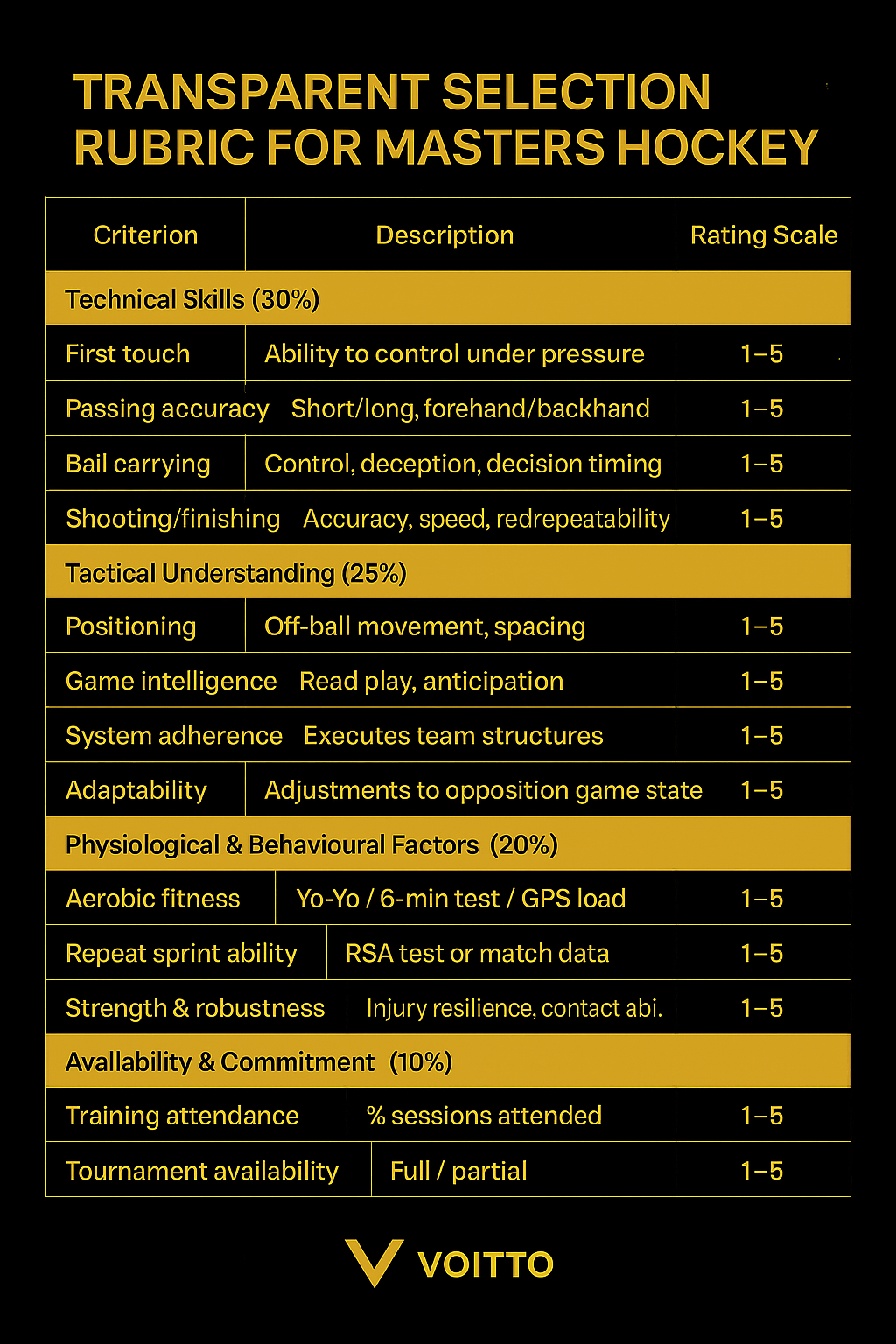

Use a transparent selection rubric to anchor decisions in pre‑defined criteria Cotterill, (2017). Selection decisions in many environments are shaped less by objective performance and more by confirmation bias and homophily. Coaches tend to favour players who fit their pre‑existing beliefs or feel familiar to them, which creates self‑reinforcing selection loops. This results in personal preference being mistaken for evidence, and it undermines both fairness and strategic alignment.

Simple basic outline of a possible masters player selection rubric

Coaches tend to select players who:

confirm their pre‑existing beliefs (confirmation bias)

feel familiar, similar, or comfortable with them (homophily)

fit their preferred narrative of what a “good player” looks like

reinforce their identity as a coach

reduce uncertainty or risk

This is not about malicious favouritism. It’s about predictable human biases that distort selection decisions and having a standardized, independent process to provide the necessary guardrails for fairness.

For a more detailed investigation of selection bias

Development & Long‑Term Pathway Decisions

Long‑term athlete development relies heavily on the brain’s ability to simulate future scenarios, a cognitive process driven by coordinated activity between the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. These regions allow coaches to project an athlete’s growth trajectory, anticipate future roles, and make decisions that prioritise long‑term potential over short‑term performance. But under acute stress, fatigue, or time pressure, this future‑simulation system becomes compromised (Klein, 1998). The brain shifts from expansive, strategic thinking into a present‑focused survival mode, narrowing attention to immediate outcomes and reducing the capacity to imagine what an athlete could become months or years down the line. In a sport like professional football, the here and now dominates thought processes. In this state, coaches unintentionally undervalue the developmental upside, and default to players who offer short‑term certainty, and avoid decisions that require patience or delayed payoff.

This is where pathway bias emerges: the athletes who need vision, imagination, and long‑range planning are the first to be overlooked when the coach’s cognitive bandwidth collapses. The result is a selection environment that rewards the “finished product” and penalises the developing athlete — not because of ability, but because of the coach’s neurological state at the moment of decision.

Mitigation

Separate long‑term pathway meetings from match‑week decision cycles to protect long‑arc thinking.

WHY COACHING IS NOW SYSTEMS ARCHITECTURE

The Interdependence of Decision Streams

These five decision streams described in the article rarely operate in isolation — they collide constantly, shaping and distorting each other every day. This interplay reflects Engel’s bio‑psycho‑social model (1977), where biological states (fatigue, stress hormones, cognitive load), psychological factors (confidence, bias, emotional regulation), and social dynamics (team hierarchy, expectations, cultural norms) interact dynamically rather than linearly. In a selection environment, this means a coach’s physical state influences their emotional interpretation of an athlete, which then colours their tactical judgement, which in turn is shaped by social pressures from parents, peers, or organisational expectations. The result is a complex, interdependent decision ecosystem where small fluctuations in one domain ripple across the others. When coaches are unaware of these interactions, they mistake a multi‑factor collision for a single, simple judgement — and that’s where bias quietly embeds itself into the selection process.

Example

Playing a relentless tactical high press increases physical load → increases injury risk → affects selection → affects social dynamics → affects psychological safety.

Modern performance environments are built around multi‑disciplinary teams — S&C coaches, analysts, psychologists, physiotherapists, medical staff, skill specialists, and leadership groups — each holding a different fragment of the athlete‑performance picture. In theory, this creates a powerful distributed cognition system,where expertise is shared across specialists and decision‑making becomes richer and more informed (Wagstaff, 2017).

But in practice, without clear filtering and integration processes, all of these inputs converge on a single bottleneck: the head coach; bless them. Instead of distributing cognitive load, the system unintentionally centralises it, forcing the coach to unify biomechanics, medical risk, tactical fit, psychological readiness, and team‑culture considerations simultaneously. Under pressure, this overload increases the likelihood of snap judgements, selective listening, and reliance on pre‑existing narratives about players.

The very structure designed to improve decision quality can, without coordination, amplify noise and overwhelm the coach’s cognitive bandwidth — making bias more likely, not less.

Mitigation

Use active simplification gatekeeping: each staff member provides a one‑page, decision‑relevant summary.

The Explosion of Athlete Data

The modern coach is drowning in information. GPS load reports, HRV trends, wellness surveys, video‑tagging outputs, heatmaps, psychological questionnaires, medical notes, tactical dashboards — each dataset is valuable in isolation, but together they create a volume of information that far exceeds human working‑memory capacity. What was once a simple observational task has become a continuous data‑integration challenge. Herbert Simon’s foundational work on bounded rationality (1971) shows that when information load surpasses cognitive limits, decision‑makers shift from analytical reasoning to heuristic shortcuts. In high‑performance sport, this reveals itself as analysis paralysis, where coaches hesitate, overthink, or default to the most familiar option simply because the brain cannot process the sheer volume of competing signals.

Instead of clarifying decisions, excessive data can blur them, overwhelming the coach’s attentional bandwidth and increasing reliance on pre‑existing beliefs or simplified narratives about players.

The irony is stark: the more data the system produces, the more vulnerable the coach becomes to bias.

Mitigation

Implement data triage:

First‑order data → directly influences decisions

Second‑order data → contextual

Noise → interesting but not actionable

HOW DECISION STREAMS COLLIDE

One of the most persistent tensions in talent pathways is the conflict between short‑term performance needs and long‑term athlete development. A young midfielder may desperately need match minutes to build game intelligence, resilience, and tactical fluency — but if the team is fighting for a playoff spot, the coach’s decision frame narrows. Under competitive pressure, the brain shifts toward short‑term risk minimisation, favouring experienced players who feel “safer” in the moment, even if this undermines the athlete’s long‑range potential. This is not a moral failing; it’s a predictable cognitive response to high‑stakes environments. Without structural safeguards, development opportunities evaporate precisely when they are most needed.

Mitigation

Planned rotation windows externalise the decision and remove it from the coach’s moment‑to‑moment emotional state. Martindale & Collins (2007) show that pre‑scheduled development opportunities — agreed upon by staff, communicated to athletes, and protected from short‑term pressures reduce bias and ensure that pathway decisions remain aligned with long‑term goals.

By embedding planned evolution-centred rotation into the system rather than relying on in‑the‑moment judgement, coaches preserve developmental integrity without compromising competitive intent. And yes, we all know “there are apps for that”. For greater effectiveness though, the rationale behind rotations within a game and across the season need to be shared and reasoned through with the playing group to ensure buy-in and minimise confusion on game days.

Tactical Ideal vs Physical Reality

Coaches often design game plans around an ideal tactical scenario for example a run and gun approach that includes high pressing, fast transitions, aggressive counter‑pressure — but the biological (and technical) reality of the squad doesn’t always match this tactical ambition. A high‑pressing system demands repeated high‑intensity efforts, rapid accelerations, and sustained neuromuscular freshness. When GPS data shows accumulated fatigue, declining high‑speed outputs, or elevated mechanical load, the physical capacity required to execute the plan simply isn’t there.

This creates a cognitive dissonance for coaches: the idea of how the team should play collides with the physiology of how the team can play today. Under pressure, many coaches cling to the tactical ideal, even when the data signals elevated injury risk or performance drop‑off. This mismatch is one of the most common — and most preventable — sources of late‑season breakdowns.

Mitigation

It may be wise to employ adaptive tactics that respect biological constraints. Gabbett (2016) demonstrated that when tactical demands exceed an athlete’s acute‑to‑chronic workload ratio, injury risk and performance volatility spike. By building tactical flexibility into the game model such as variable pressing triggers, situational mid‑blocks, or controlled rest‑defence structures, coaches can maintain strategic intent while aligning with the squad’s physiological state.

This approach reframes tactics not as rigid ideology but as load‑responsive decision‑making, ensuring the team plays in a way that is both effective and biologically sustainable.

Psychological Safety vs Competitive Intensity

High‑performance environments demand intensity, accountability, and honest feedback but when feedback is delivered harshly or without emotional attunement, it can trigger limbic‑system threat responses in athletes. Research by Arnold & Fletcher (2012) shows that when athletes perceive criticism as personal, unpredictable, or humiliating, the amygdala activates, cortisol rises, and the brain shifts into a defensive state. In this mode, working memory, motor learning, and decision‑making all deteriorate. Instead of absorbing the message, the athlete protects themselves from it. This creates a paradox for coaches: the harder they push, the less the athlete learns.

Over time, repeated threat responses erode trust, reduce risk‑taking, and suppress the very competitive behaviours the coach is trying to cultivate. It also threatens the players health by the constantly elevated SNS triggers. Psychological safety isn’t softness — it’s the neurological foundation that allows athletes to tolerate challenge, process feedback, and adapt under pressure.

Mitigation

Using the support → challenge → support communication model preserves psychological safety while maintaining competitive standards. The initial support regulates the athlete’s threat response, the challenge delivers the performance message with clarity, and the closing support ensures the athlete leaves the interaction feeling capable rather than diminished. This structure keeps the brain in a learning‑ready state, allowing intensity without triggering shutdown.

Fairness vs Winning

Few things fracture a team faster than perceived unfairness. When athletes believe selection decisions lack transparency or consistency, cohesion erodes, trust collapses, and players shift from collaborative mindsets to self‑protective behaviours. Cruickshank & Collins (2015) show that fairness perceptions are one of the strongest predictors of team harmony, leadership credibility, and athlete buy‑in. This isn’t just emotional; it’s neurological.

Unfairness triggers SCARF‑model threat responses, particularly in the Status, Certainty, and Fairness domains. When these needs are violated, the brain activates limbic threat circuits, reducing openness, learning capacity, and willingness to accept role assignments. Athletes begin scanning for inconsistencies, interpreting neutral feedback as criticism, and withdrawing effort or communication. In this state, even well‑intentioned coaching decisions are filtered through a lens of suspicion.

Fairness isn’t a “soft” concept — it’s a biological prerequisite for trust, cohesion, and sustained performance

Mitigation

Communicating role clarity and selection rationale directly addresses the SCARF triggers. Clear explanations restore Certainty, transparent criteria reinforce Fairness, and acknowledging an athlete’s contribution protects Status. When athletes understand why a decision was made — even if they disagree with it — the threat response diminishes, and the team remains aligned.

This simple communication discipline is one of the most powerful tools a coach has for preserving cohesion under pressure.

Data vs Intuition

Intuition in coaching is not guesswork, it’s a kind of compressed pattern recognition, built from thousands of hours of exposure to game situations, athlete behaviours, and contextual cues (Klein, 1998). When used well, intuition allows coaches to detect subtle shifts in momentum, confidence, or tactical flow long before the data catches up. But intuition only functions effectively when cognitive bandwidth is available. In environments overloaded with GPS metrics, wellness scores, video clips, and medical data, the brain’s ability to access these deep pattern libraries becomes suppressed. Excessive data noise drowns out the intuitive signal. Under overload, coaches either ignore their intuition entirely or over‑rely on it in a reactive, uncalibrated way. The challenge is not choosing between data and intuition — it’s ensuring that intuition remains a high‑quality input rather than a stressed‑state shortcut and its resultant potential clusterfuck.

Mitigation

Treat intuition as a signal to investigate, not a verdict. When a coach feels something — a player looks off, a matchup feels wrong, a tactical shift seems necessary — that intuitive cue should trigger a brief, structured check against relevant data rather than an immediate decision. This preserves the value of intuition while protecting against bias. It also aligns with dual‑process decision models: intuition (fast thinking) raises the flag, and analysis (slow thinking) verifies it. In practice, this creates a balanced decision ecosystem where neither data nor intuition dominates, and both remain functional under pressure.

WHY MODERN COACHING IS COGNITIVELY OVERWHELMING

Working Memory Limits and Cognitive Load

Working memory is very limited as it can only hold a small number of information chunks at any one time, and once that limit is exceeded, decision quality drops sharply (Sweller, 1988). In high‑performance sport, coaches are often asked to juggle tactical plans, opposition tendencies, athlete readiness data, injury risks, and live match dynamics simultaneously. When too many inputs compete for attention, the brain shifts from deliberate reasoning to reactive processing. Subtle cues get missed, irrelevant details get overweighted, and decisions become inconsistent or overly simplified.

This is the cognitive bottleneck at the heart of many selection and tactical errors: the system demands more than the human brain can carry in working memory, especially under stress.

Mitigation

Reduce inputs

Strip information down to the bare essentials for the decision at hand. Fewer signals means higher fidelity.Chunk information

Group related data into meaningful clusters so the brain processes one “unit” instead of many.Use visuals

Diagrams, dashboards, and spatial layouts offload cognitive effort, freeing working memory for actual decision‑making

Decision Fatigue and Risk Bias

Across a training week or match day and in particular, a tournament, coaches make hundreds of micro‑decisions — selection tweaks, tactical adjustments, medical clearances, rotation choices, feedback moments, substitutions, and role assignments. Baumeister’s work (2013) shows that repeated decision‑making progressively degrades cognitive control, reducing the brain’s ability to evaluate options clearly and resist impulsive or risk‑averse shortcuts.

As decision fatigue accumulates, coaches become more likely to choose the familiar option, avoid uncertainty, or default to conservative, low‑variance choices. This shift isn’t a character flaw, it’s a predictable neurological response to cognitive depletion. In high‑performance environments, this means that the timing of decisions can be as influential as the content of decisions.

When fatigue sets in, risk tolerance narrows, creativity drops, and bias becomes more likely to slip into the process unnoticed.

Mitigation

Batch decisions

Try to group similar decisions together so the brain enters a single decision frame rather than switching contexts repeatedly. Eg. warm up and recovery plan in advance with alternate routines as physical fatigue encroaches on players.

Protect your own recovery

Cognitive recovery is as important as physical recovery; rested coaches make clearer, less biased decisions. How often do we witness the exhausted state of martyr coaches looking and sounding more and more unravelled as a tournament week progresses? Rest; eat and drink healthily then get away from the event at every opportunity and socialise with non hockey people.

Use routines

Pre‑defined decision protocols reduce cognitive load, preserve consistency, and protect against fatigue‑driven risk aversion.

These strategies help maintain decision quality across the week and reduce the hidden drift toward conservative, biased, tired choices that emerges when cognitive resources run low.

Prefrontal–Hippocampal Planning Under Load

High‑quality planning depends on the brain’s ability to simulate future outcomes, a process driven by coordinated activity between the prefrontal cortex (strategic reasoning, long‑range thinking) and the hippocampus (memory integration, scenario construction). Kahneman (2011) describes this as the brain’s capacity to run mental “future movies; projecting how decisions today will play out across days, weeks, or seasons. As you may expect, under cognitive load, stress, or fatigue, this simulation system degrades. The prefrontal cortex loses bandwidth, the hippocampus retrieves fewer relevant patterns, and planning collapses into short‑term, reactive thinking.

Coaches in this state overvalue immediate constraints, undervalue long‑term consequences, and default to decisions that feel safe in the moment but misaligned with future goals. This is the neurological root of many pathway errors: the system designed for foresight becomes overwhelmed and shifts into present‑tense survival mode.

Mitigation

Create structured planning windows

Protect the time when cognitive load is low so long‑range decisions are made with full prefrontal capacity, not in the chaos of training or match prep.Make the effort to define and occupy a healthy quiet space; practice mindfulness.

Use scenario planning

Build and record some of the most probable pre‑constructed future pathways (“if X happens, we do Y”) so the brain doesn’t need to generate simulations from scratch under pressure.

These practices preserve the integrity of long‑term thinking and prevent load‑induced drift toward short‑termism.

Loss of Intuition Under Data Pressure

Intuition is not the opposite of data — it is the compression of thousands of past data points into rapid, experience‑driven pattern recognition (Klein, 1998). Expert coaches develop intuitive accuracy because they’ve seen enough repetitions to detect subtle cues that never appear in spreadsheets: body language shifts, micro‑timing errors, confidence fluctuations, relational dynamics, or tactical “feel.” But when the environment becomes saturated with metrics, dashboards, and constant updates, cognitive bandwidth gets consumed by surface‑level data processing. The intuitive system — which relies on quiet, background pattern matching — gets drowned out. Under data pressure, coaches either ignore intuition entirely or misinterpret it, treating stress‑induced impulses as “gut feel.” The result is a paradox: the more data the system produces, the less access coaches have to the very expertise that makes them valuable.

Mitigation

Use a dual‑process model where intuition and data work together rather than compete. Intuition raises the initial signal (“something feels off”), and data provides the verification (“is this supported by hard facts and expressed in performance patterns?”). This protects against both extremes, blind intuition and blind data, and preserves the coach’s ability to link deep experience with objective information.

It can help keep intuition functional, calibrated, and anchored in reality rather than suppressed by noise.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abernethy, B. (1990). Expertise and perceptual‑cognitive skill in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences.

Arnold, R., & Fletcher, D. (2012). Psychosocial factors associated with performance. Journal of Sports Sciences.

Baumeister, R. (2013). Decision fatigue. Social and Personality Psychology Compass.

Bourdon, P. et al. (2017). Monitoring athlete training loads. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance.

Boyd, J. (1976). The OODA Loop.

Carling, C., Williams, A., & Reilly, T. (2005). Handbook of Soccer Match Analysis.

Chase, W., & Simon, H. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology.

Cotterill, S. (2017). Leadership in Sport. Routledge.

Cruickshank, A., & Collins, D. (2015). Culture and leadership in elite sport. Journal of Sports Sciences.

Engel, G. (1977). The bio‑psycho‑social model. Science.

Endsley, M. (1995). Situation awareness theory. Human Factors.

Gabbett, T. (2016). The training–injury prevention paradox. British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Impellizzeri, F. et al. (2019). Load monitoring in team sports. Sports Medicine.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Klein, G. (1998). Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions.

Lyle, J. (2002). Sports Coaching Concepts.

Martindale, A., & Collins, D. (2007). Coaching effectiveness. Sport Psychologist.

Nash, C., & Collins, D. (2006). Tacit knowledge in coaching. Journal of Sports Sciences.

Reardon, C. et al. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Rice, S. M., Parker, A. G., Mawren, D., Clifton, P., Harcourt, P., Lloyd, M., … Purcell, R. (2020). Preliminary psychometric validation of a brief screening tool for athlete mental health among male elite athletes: the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(6), 850–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1611900

Simon, H. (1971). Designing organizations for an information‑rich world.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load theory. Cognitive Science.

Wagstaff, C. (2017). Organizational Psychology in Sport. Routledge.

Williams, A., & Ford, P. (2008). Expertise and decision making in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences.